Encouraging change: a wheely big task…

A short while ago a friend of mine started volunteering with a local community project* based out of her home town.

My friend owns an organic local produce stall that she runs out of an upscale food market in Boston. She’s also started supporting a local non-profit whose goal is to help law enforcement officers watch their weight.

Apparently there’s an obesity epidemic among law enforcement officers across the United States—and, contrary to what we see on television (who would have thought?), law enforcement officers are far more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than they are from anything a criminal might do to them. So, my friend started running cooking classes for law enforcement officers, showcasing quick and simple recipes that were also good for the heart. She also offered a discount so local law enforcement personnel could buy produce from her store at cost price.

By the time we spoke, she’d run three or four workshops—each with about 10 officers—officers who, by all accounts had a great time at the cooking classes (unsurprising given they got to eat my friend’s food afterwards and she is, without a doubt, the best cook I know).

“How many of the officers have been back into the store to buy produce?” I asked (my cynical evaluator brain fairly sure I knew the answer). She paused, thought for a moment then answered: “You know, not a one.”

The trouble with people…

As an evaluator, this news wasn’t particularly surprising. Many social programs are, at their heart, efforts to change peoples’ behaviour. Teacher training programs, health promotion initiatives: so many social programs rest on changing an individual’s behaviour. And, as pretty much any human will tell you: changing human behaviour is notoriously tricky.

A cooking program like this is no different: this particular program tries to change the way law enforcement officers shop, cook, and eat—the problem being, there’s a lot that goes into converting workshop attendance into kitchen table habits.

What to do?

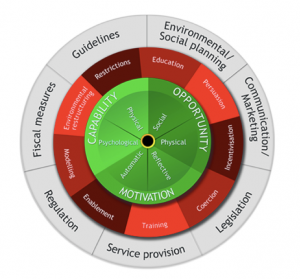

Two handy heuristics come to mind as helpful ways of thinking about the factors that influence attempts to change behaviour: (1) Michie and colleagues’ Behavior Change Wheel, and (2) Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model of development.

The Behavior Change Wheel

Research on behaviour change says that people need three things to change their behavior.

- They need to be motivated to change [i.e. they need to think the new behaviour is a good idea; that doing it will have positive effects; and, most importantly, they need to wantto make the change]

- Additionally, people need to have right skills [i.e. they need the time, resources and capacity to make the change]

- And finally, they need to be in an environment that the supports the change [i.e. they need to be surrounded by people, institutions, organizations who encourage, expect and support them to make the change].

Initiatives that target only one or two of these three elements often fall short because they overlook the critical levers that make behaviour change possible.

Image source: http://www.behaviourchangewheel.com/about-wheel

In their book The Behavior Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions, authors Susan Michie, Lou Atkins and Robert West summarize 19 frameworks for behaviour change, extracting these three high level levers as the common thread.

The authors also identify a series of 9 common interventions that are used to target the three levers of change–creating a fabulous resource for program designers and evaluators alike.

Ecological models

Before the Behavior Change Wheel, developmental psychologist Uri Bronfenbrenner wrote that individuals do not exist in isolation.

Instead, we’re like onions, our daily behaviors and beliefs shaped by layer upon layer of influences.

We’re influenced, for example, by our immediate environment (including our families, colleagues, friends). We’re also influenced by the people and institutions that these people interact with, including schools, industries, public transport systems, as well as broader societal influences like state and national culture, the mass media, political systems etc.

Attempts to shift an individual’s behavior are more likely to succeed when they target multiple layers of the onion instead of only one.

In my friend’s case, the law enforcement officers’ families might be the most useful layer to target. A few key questions immediately come to mind:

- Who does the shopping in these households?

- Who does the cooking?

- Are the law enforcement officers the people who do the shopping and the cooking? If not, there’s no clear thread between what they learn in the cooking classes and what makes its way onto the kitchen table.

Looking more broadly—where do our officers live? Can they access the market easily? Or do they need to go out of their way, outside their usual routines to get to her stall to buy the food they need to make the new foods?

And then?

Will either of these models guarantee a program designer can create a program that leads to behavior change? Of course not. But using these heuristics might be a way to keep in mind the multitude of factors that shape the way an individual behaves—and therefore the many factors that need to shift in order for us to see sustained change at the individual level.

*Some elements of the project adapted for anonymity.