No straight line to change

A friend of mine gave up coffee about a year ago. He gave it up primarily because he didn’t want to be addicted any more: didn’t want to wake up in the morning feeling like he needed a coffee hit before his brain switched on.

Needless to say, the giving up process was a little rocky. He got hit with the flu just as he decided to kick the caffeine and so spent a week in bed, suffering from both the aches and pains of the flu as well as pounding migraines from caffeine withdrawal.

In short, his wellbeing took a turn for the worse before anything got better.

There were also a few rough patches when he fell into old habits, ordering an espresso when out with friends, saying yes when people offered him a cuppa—just because it sounded like a good idea at the time.

Twelve months on he’s caffeine free, full of energy and loving it, but the path to his caffeine-free existence was anything but straight.

Why should evaluators and the non-profit community care about my weird friend who gave up coffee?

Change often isn’t linear, but our evaluation methods don’t always reflect that.

Imagine we’d done a pre/post test of my friend’s experience, comparing his subjective wellbeing one week before giving up coffee to his subjective wellbeing one week after giving up coffee. What’s the effect of going caffeine free? Pain, torment, and a big, whopping headache.

Now, I realize this evaluation plan sounds foolish, but that’s only because we know (or suspect) that giving things up can be hard, and people experience things like withdrawal symptoms—particularly in the short term.

The point is, most change efforts have their own trajectory: we just don’t always know what these trajectories are, so it’s hard to embed them into evaluation methods.

Design sensitivity

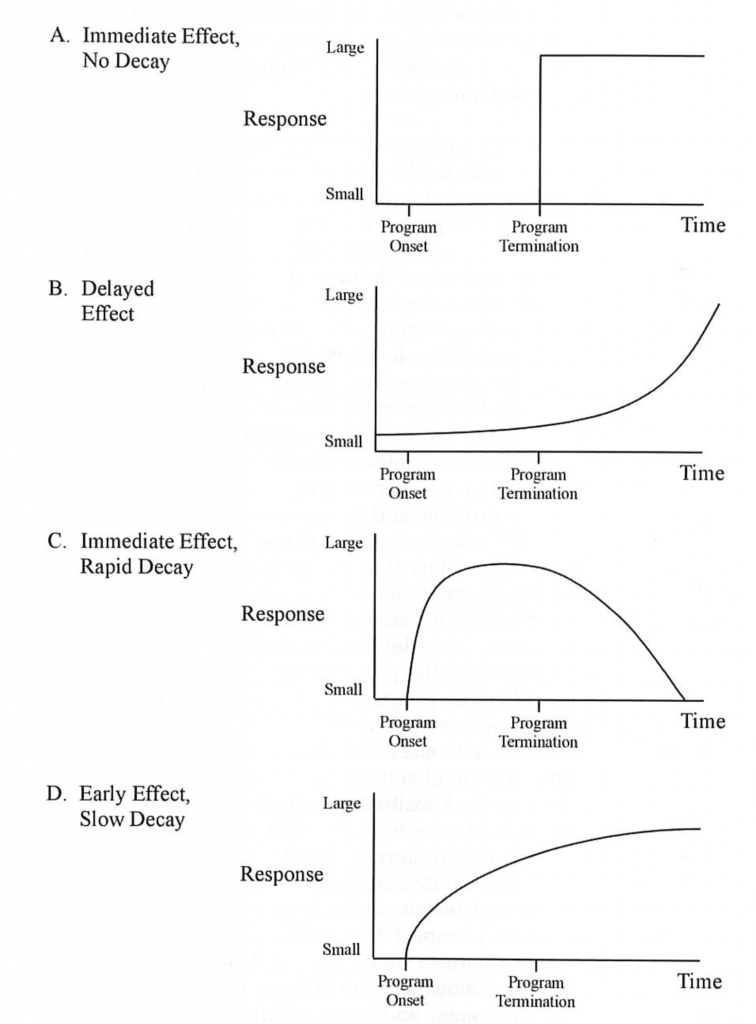

Back in 1990, evaluation guru Mark Lipsey described a series of possible program-effect decay functions. These modelled (in theory) the relationship between time (i.e. when a program began and finished), and when (in theory) the communities who took part might experience their effects.

His proposed models included scenarios where:

- interventions had immediate effects, and were sustained over time

- interventions had a delayed effect

- interventions had an immediate effect, but where change was not sustained at all

- interventions had an early effect, but these changes slowly dissipated over time (see the image below for graphical representations).

Image source: Donaldson, S. (2007). Program Theory-Driven Evaluation Science: Strategies and Applications.

Timing evaluation data collection

Consider the implications of only this limited set of program effect models for the timing of evaluation-related data collection. What if program effects are delayed but we collect data at the project end-point? What if program effects decay but we capture them at their high point? What if effects are generational but we stop longitudinal tracking at 10 years?

Evaluations can substantially over or under-estimate the effects of social programs simply because of their timing. Problem is: we don’t know how to better time our evaluations because we haven’t systematically mapped the trajectories of change.

What to do?

What if we had a centralized resource, based on systematic research about social change interventions—specifically designed to make it easy for evaluators to understand the typical change trajectory for the program they’re evaluating.

This is one of our upcoming projects at the Center for Research Evaluation. We’re trying to understand common trajectories of change and how they apply to common social programs. We’re hoping to turn this into a resource that others can use—in the hopes that this might help us better time our evaluations to the trajectories of change. Get in touch if you’d like to collaborate.