Looking for trouble—on purpose

You’ve probably heard the fable about the frog in the pot of water: Put a frog in boiling water and he jumps right on out. Put your frog in some nicely temperate water then turn up the heat and he’ll relax like it’s a spa day until he’s good and boiled.

Curiously, I recently learned that this reptilian fable just isn’t true (thanks Dr. Karl). Apparently, frogs can tell within increments of 2 degrees (farenheit) that water is getting hotter. As the temperature slowly increases, frogs will become “more and more active” in their efforts to escape.

Notwithstanding the fable’s factual grounding, it offers up a useful lesson I’d like to highlight here. Lesson 1: nobody wants to be the frog who gets boiled because they didn’t see trouble coming.

The fact-checked version also offers up another useful lesson that gives me reason for cheer. Lesson 2: we’re smart enough to see when trouble’s coming.

So what does this have to do with evaluation? Well, a great deal.

Evaluation is political. Money, resources, and power come into play as part of standard evaluation processes. As a result, our work can have practical implications for real, often vulnerable, people.

All of this is to say that evaluation is complex, and things can go wrong. In fact, sometimes, they can go horribly, horribly wrong. But—fear not, because (1) we know that nobody wants to be the frog who gets boiled. And, (2) we know that we’re smart enough to see when trouble’s coming.

So how do we know if trouble’s coming in an evaluation? In short, we look for risk factors.

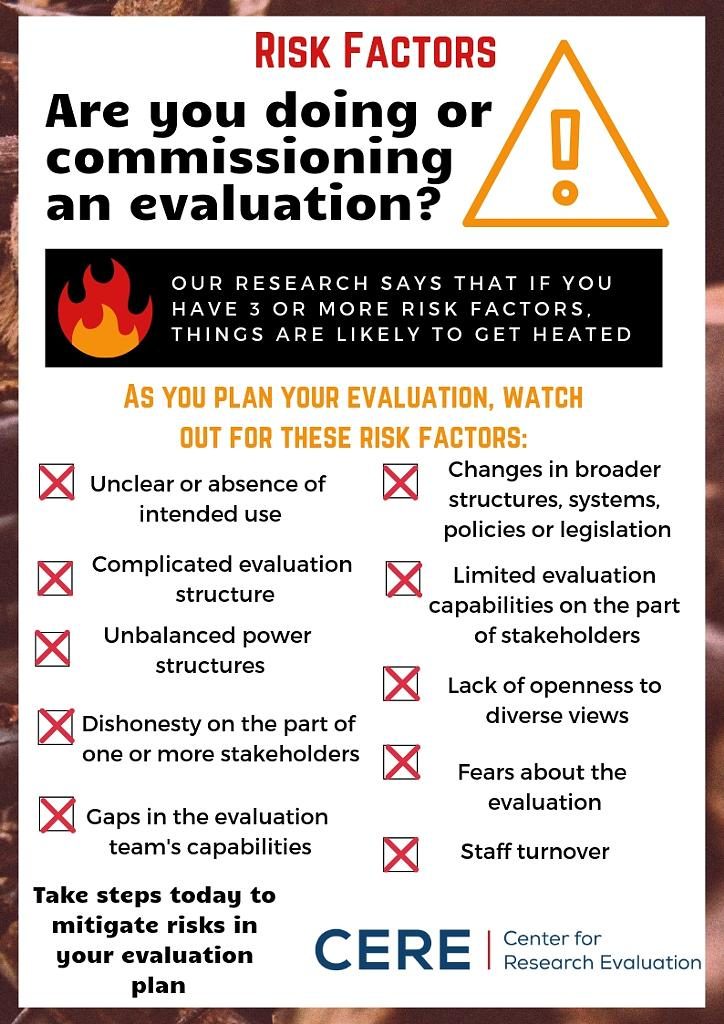

Risk factors in evaluation

Last year, I interviewed 35 evaluators with experiences across the globe. I asked each of these evaluators to share two real-world evaluation scenarios: one where things went swimmingly, and another where things went (sometimes horribly) wrong. Once I had these scenarios, I separated them into two piles and looked for factors that separated the two from each other. These are our risk factors.

Things seemed to go wrong when:

- Commissioners had no idea why they were doing the evaluation—or whether they would use the results.

- There were complicated accountability and reporting structures, like an evaluator reporting to one person on technical matters, and to another person completely on budgetary matters.

- There were clear imbalances in power—whether between the evaluator and the client, or between the client and those who receive their services.

- A person or persons were dishonest.

- There were gaps in the evaluation team’s capabilities as they related to this, specific evaluation.

- Change was afoot. Specifically, there was change in the broader structures, policies, systems or legislation that governed the program being evaluated.

- The stakeholders had limited evaluation experience.

- There was a lack of openness to diverse views, particularly among those in positions of power at the client organization.

- People were afraid of the evaluation and its findings, and

- There was staff turnover, either in the evaluation team, or in the program team.

Now, many of these features occur regularly in evaluation situations. The key question becomes: how many of these risk factors do you have at play in a given situation? In my analysis of these 70 scenarios, problems tended to occur when three or moreof these risk factors were in place.

Much like the risk factors used to predict problematic health or youth outcomes, evaluators seemed to be able to withstand individual instances of risk. These were challenging, but could be overcome. Instead, problems emerged when there was cumulative risk—multiple, often intersecting issues that added to the already complex nature of evaluation practice.

What does all this mean for you in your evaluation practice?

I’d suggest three things:

- Don’t be the frog who gets boiled

- Be smart enough to know when trouble is coming

- Use this list of risk factors to help you figure out when trouble is coming so you can take steps to mitigate the risks ahead.